A conversation with Manfred Wenzel about the origins, foundation and future of TEK TO NIK Architekten.

Buildings can be planned. An architecture company can’t. How did you get started?

MW: We just wanted to get started and stand on our own two feet. We didn’t have a business plan, but we had a common inner attitude. So Didi, Stefan and I founded our architecture company together on July 4, 1999. The date is easy to remember, it was our personal Independence Day.

What was the common inner attitude?

MW: First of all, we trusted each other and our skills. We saw each other as complementary. We all had our own profile. What we had in common was a passion for learning and growing, discovering and inventing. But perhaps the most important thing was that we wanted to create new forms of collaboration. We always wanted to combine ourselves in new ways. We were not interested in routines. Nor were we interested in landing as many assignments as possible. And we weren’t just interested in architecture and building construction. We wanted to do more than just pour concrete. We wanted to deal with all aspects and details that are good for a place and a city.

How did the foundation come about? What came before?

MW: Today I would say that the beginning of TEK TO NIK was the logical next step in a long collective journey. Most of us had already known each other for around ten years at the time, through our studies at Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences. This included Dieter, Kathrin, Marcus, Olaf, Matthias, Verena, Tillmann, Frank, Lasse and Rudolf and others around us. We were a kind of network that could work together in a wide variety of combinations.

It sounds a bit like a group of artists – everyone does the same thing, but you somehow feel connected. Or were you a group of specialists?

MW: It’s hard to say. That’s not really true either way. We were least of all a group of artists. I would say we were individualists who believed we could achieve more together and who also simply enjoyed working together, discussing, debating and criticizing. The closest thing to a jazz band.

The “Band” TEK TO NIK Architects, ca. 2005

So there were specializations after all?

MW: Of course there were. The individual profiles also included individual skills. Many of us had previously trained as bricklayers, concrete workers, draughtsmen, carpenters or joiners. I and all of us had always been just as interested in craftsmanship and construction expertise as we were in design and architectural aesthetics. We wanted to build beautifully, sensibly, well and durably.

Was there a professor during your studies in Frankfurt who had a particular influence on you?

MW: Nikolaus Kränzle was important for us. Nikolaus taught us in the foundation course, in building science and building construction. That was the spark, the first enlightenment about the problems of good building culture. And luckily it continued with him in the main course, because he also offered to continue. This created a sense of cohesion among the particularly committed students. We worked on stone designs and design tasks. It was like a master class, with lots of conversation and many critical and detailed discussions. Nikolaus was the “boss” for us. With him, studying architecture had intellectual aspirations. Through him, we discovered architecture as a comprehensive discipline that included design, material, construction, life, purpose and people as social beings.

Did Professor Kränzle co-found TEK TO NIK Architekten, so to speak?

MW: That would be a bit too much to say. But well, Nikolaus Kränzle is part of our foundations somewhere. We found each other as a group with him because we were studying as a group. We had sort of agreed on that. We wanted to continue together as a group because our discussions with each other were exciting. And we spurred each other on to top performance. The “boss” noticed that we were particularly committed students and brought us into contact with older students, Dieter, Stefan and Thomas. They had been studying for some time and were also exceptionally talented and committed, but didn’t have the motivation of a group. They then joined us and we immediately benefited from each other.

What happened after your studies?

MW: After graduation, we all went in very different directions.. Everyone found a job somewhere else. I joined the Gerhard Balser architectural partnership. The three partners were students of Egon Eiermann. The office was influenced by this, was cool, had its own culture and the high architectural standards of the great Eiermann. I became a second-generation Eiermann student, so to speak, and at the same time I learned a lot about running an architecture company and dealing with public authorities.

And what about the other group members?

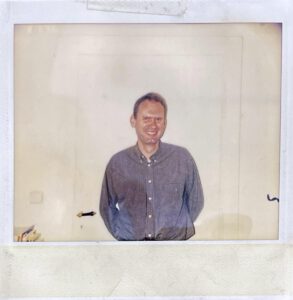

MW: Stefan was unhappy in an office in Berlin. I told him to come here to Frankfurt. I also put Dieter in touch with the Balser office. When Gerhard Balser turned 70, which was in 1999, we the youngsters were supposed to take over the office. And we thought, why not start something of our own? And then we became TEK TO NIK Architekten. When Hubertus von Allwörden, Balser’s partner, visited us in our office once, he said that you were the grandchildren’s office. In other words, the third office in the Balser family of architects. We saw that as an honor and a distinction, and the title “grandchildren’s office” still makes me a little proud today.

There is a lot of tradition in the new company you founded back then. But wasn’t that also a burden?

MW: Definitely an additional obligation to never deliver below certain standards. And we wanted it to be tough and demanding. If you look closely, you will find traces of Egon Eiermann in our work, which we got to know through Balser and Allwörden. To this day, we work meticulously on “correctness” and clear structures and don’t let crooked solutions out of the house. But these were not the only influences. The job at Christoph Mäckler, for example, also had a profound impact on me, as he was one of our architectural heroes. And the comprehensive view of architecture that we got to know with Nikolaus. How architecture influences our social life, our health and our environmental footprint – all of this has become increasingly important since we founded the company.

And how did the name TEK TO NIK come about?

MW: The three of us founded the company, Stefan Burger, Dieter Gutsche and I, so it was a three-man decision. The first idea is always to combine the first letters – that would have been BGW for us. But a three-letter office like Accountants and lawyers was a no-go. And then one of us had Hans Kollhoff’s “Über Tektonik in der Baukunst” (“On tectonics in architecture”) in our hands. And we thought that was perfect, because as an office we wanted to become a kind of platform that others could dock onto. On top of that, Nikolaus had studied with Hans under Egon, so that was also a confirmation of the line of tradition on which we saw ourselves.

Another return to the roots. To the ancient Greek word core of architecture …

MW: Yes, that’s right. We are inconceivable without the classical problems of architecture – scale, proportion, rhythm, systematics, purpose and so on. Some people have used classical modernism to suddenly feel free of it. TEK TO NIK has been an office for 25 years, where we never wanted to make things so easy for ourselves.

So in our first office in Brückenstraße, we were always in touch with the city reality

And did more people join?

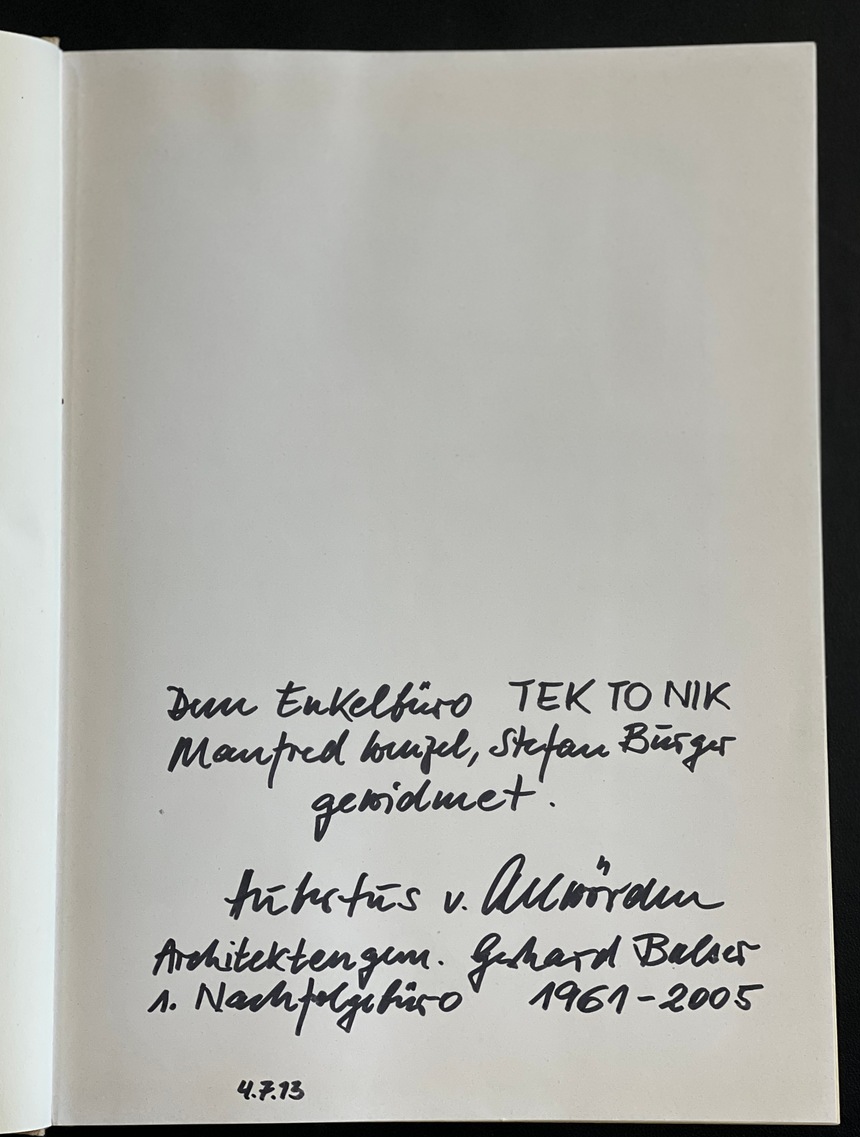

MW: Yes, the project grew, also with the necessary people around it. My girlfriend Maja quit her job because she wanted to do all the accounting. Lera designed our CI. Kai, Gregor and Böhm took over the IT. One day we needed help with the copywriting, so Fritz joined us as a freelancer, Andreas Stimpert for the photos.

Each new person brings new exchanges, input, new questions …

MW: Absolutely. Over the past 10 years, we have repeatedly brought in young international people, sometimes students directly from the Städelschule. Quite deliberately, because new external impulses can only be good. Besides, an architecture company is always a point in a network. We work together with countless other firms, including technical universities. No architect achieves the big goal alone, at least not if building quality is the goal.

And there have also been farewells over the years?

MW: Yes, that’s part of it. If TEK TO NIK sees itself as a platform for good architecture and not simply as the office of architects XYZ, then that also means openness in the composition. I miss some of them, how we fought together for the right solutions. Unfortunately, it is no longer possible to return to Dieter and Eckbert. They died far too early, but they are still alive in me.

The original sources from which TEK TO NIK emerged, what significance do they now have for the future?

MW: They continue to bubble up. In fact, I think their significance is even more central to us today. I think that with every year I understand better what we are up to here and what our core consists of.

Isn’t every major project also a learning opportunity?

MW: Sure. And I’ve come to realize that every task is a group project. Collaboration is essential in architecture. This realization has deepened for me. Today, we work and live this in the office and in the future we would like it to become even more intense. Anyone who joins us must quickly feel and experience this.

It’s like an orchestra, let’s say the Berlin Philharmonic, where new musicians keep coming in and others leave. And the spirit must always be maintained …

MW: Good comparison, although the orchestra is too hierarchical for me and we don’t all always play the same piece. Otherwise it’s true that everyone feels responsible for the joint result, enjoys their role and grows with it. And this spirit is in all of us, at least not just in the managing directors. There is perhaps an organizational and creative core, which today consists of Manuela, Jan, Andreas, Arne, Jorge, Maja and me as the person who has been there the longest. But the core is open to all sides and anyone who really wants to can get more autonomy with us or simply take on specific tasks.

Have the architectural tasks actually changed in the last 25 years?

MW: Well, what doesn’t change in 25 years? The standards have increased. But that is perhaps not as important as the issues of sustainability and urban development. Sustainability and energy efficiency are no longer just a question of meeting standards through façade technology, but are an overall issue. The German Sustainable Building Council was founded in 2007. It was only in 2007, not 1970 or 1980, that a completely new certification system was created. We were one of the first to follow it and receive gold certification for the overall measures (Triton, 2010-2013). I would say that the complexity of completed architecture has increased. Today, good architects have to have even more technical skills or build them up around themselves.

At the “German Natural Stone Award” ceremony, 2015

And urban development is the second major topic that has become more important?

MW: Yes, exactly. The debates are intense today, right across Europe. Ideas are being sought everywhere as to how the mistakes of the past can be ironed out and how the new needs for traffic-calmed urban life can be met. It’s about less car traffic, family friendliness, social housing, peaceful cities in which everyone can feel comfortable and no group is marginalized. We have a lot to do in Germany over the next few decades, and we can learn from the pioneers.

It’s very much a political issue over which architects have little influence …

MW: Yes, unfortunately the topic of “liveable cities” is over-politicized. We should look objectively and analytically at what can be done and then implement it step by step. Our Grüne Gasse (MAIN YARD of the OrT Group) is a small example of the creation of new social spaces in the middle of an urban problem zone that seemed unchangeable for decades. But that’s how it is now: Even the revitalization of a building or an entire block is no longer just about insulation, wood laminate and a colorful facade, but requires an overview of the possibilities, new ideas and goals..

There is still a lot for TEK TO NIK to do …

MW: Yes, absolutely. In fact, we’ve only just begun.

The interview with Manfred Wenzel was conducted by Fritz Iversen, who has been writing for TEK TO NIK Architects for more than 20 years.